Genetic Algorithm - Solving Assignment to Demographics

Introduction

I worked at a marketing tech company where we encountered a challenging real-world problem. I successfully solved it using a Genetic Algorithm. In this post, I’ll describe the problem and the solution I implemented. A Jupyter notebook is linked at the end for you to explore further.

Jupyter Notebook

The Jupyter Notebook can be played with here. Alternatively, you can just view the HTML version here: Genetic Algorithm Demographic Balancing.

Problem Statement

The Business

I worked with an “IHUT” (In-House Usage Testing) company that managed a user base of about 50,000 individuals. These users were sent physical boxes containing products to test. They would then provide feedback, allowing companies to test products before a broader public release.

The Challenge

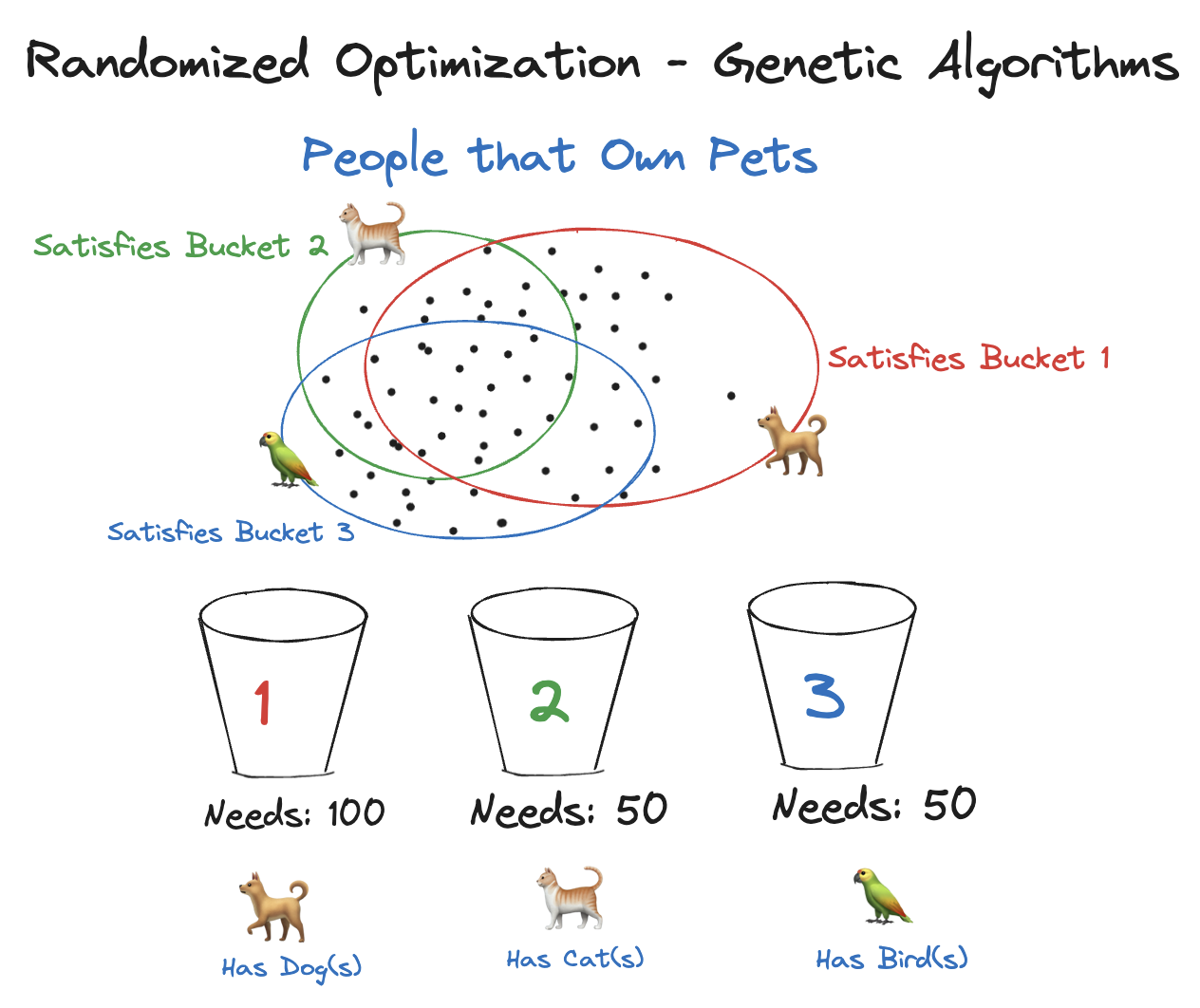

Companies often sought analytics from various specific groups, with the potential need for different box preparations for each group. The issue arose because these target demographics were not mutually exclusive. Demographics might include factors like age, gender, employment status, education level, and preferences.

For example, consider a pet-food company wanting to test a new pet food type. We might need to ship 100 Dog-Food Boxes to people with dogs, 50 Cat-Food Boxes to people with cats, and 50 Bird-Food Boxes to people with birds. However, some individuals might own both dogs and cats or other combinations, leading to a potential shortage in specific demographics. This situation presents a constraint satisfaction problem.

In the real world, the challenge scales with more competing demographics, making optimization complex and traditional search algorithms less effective.

Figure: Demographic Selection Constraint Satisfaction Problem

Figure: Demographic Selection Constraint Satisfaction Problem

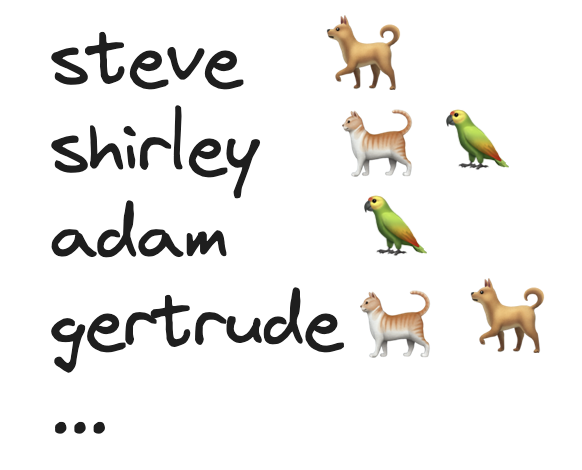

An example of defining which of the demographics each individual can possibly fall into.

An example of defining which of the demographics each individual can possibly fall into.

Genetic Algorithms

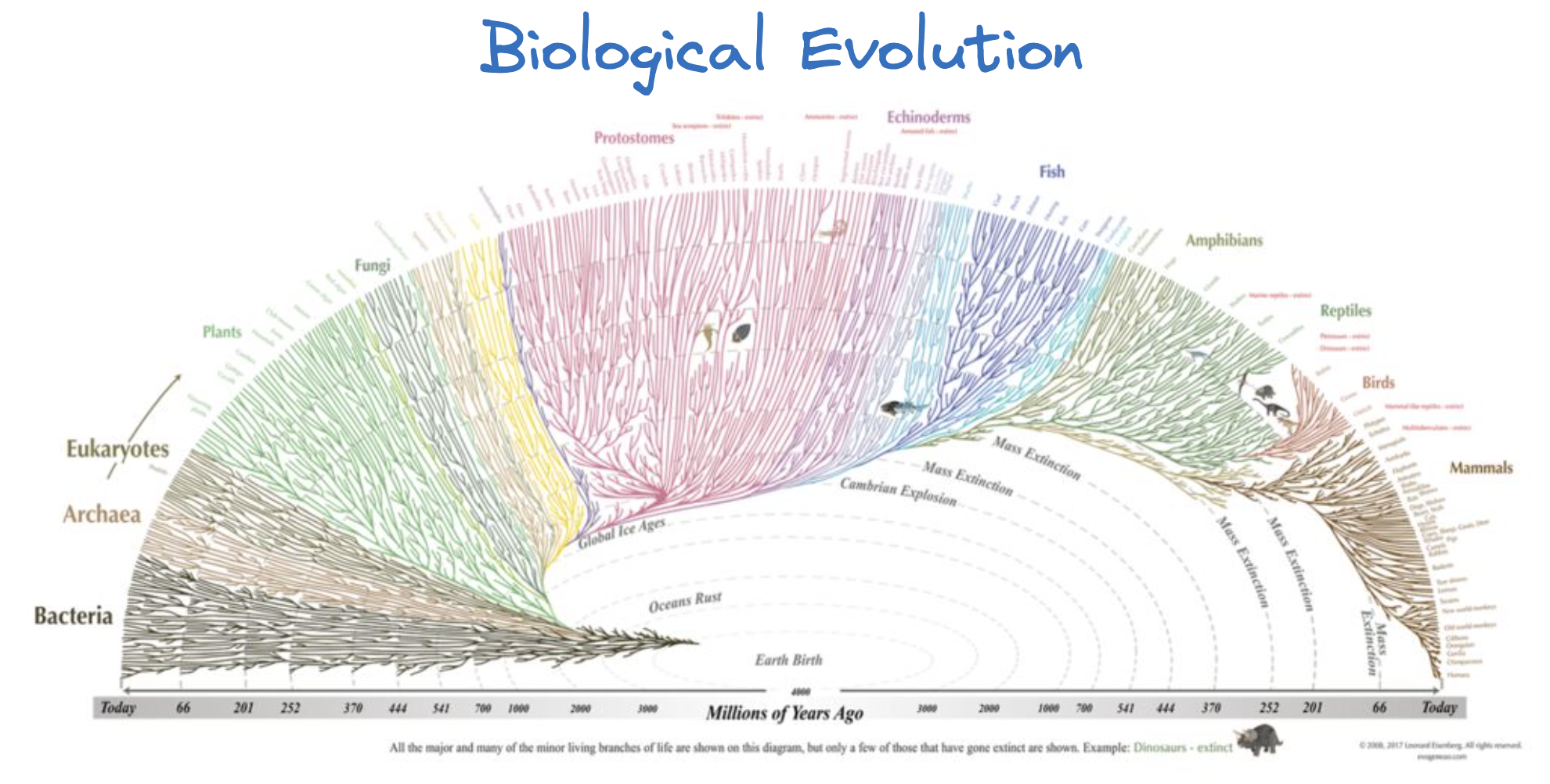

Genetic Algorithms (or Evolutionary Algorithms) are a class of algorithms which are inspired by biological evolution. The idea of “survival of the fittest” is used here. In this algorithm, you define what it means to be “fit”. This is the fitness function, and it is the basis by which an individual in a population is judged. Those who are fittest have a greater chance of survival, and therefore propagating their offspring and creating the next generation of individuals. New offspring are created using a combination of Mutation and Crossover.

The Evolutionary Algorithm created the vast richness of life on our planet.

The Evolutionary Algorithm created the vast richness of life on our planet.

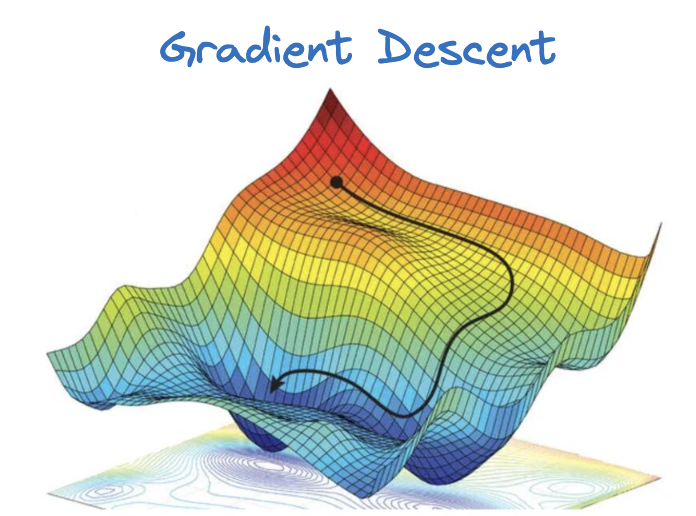

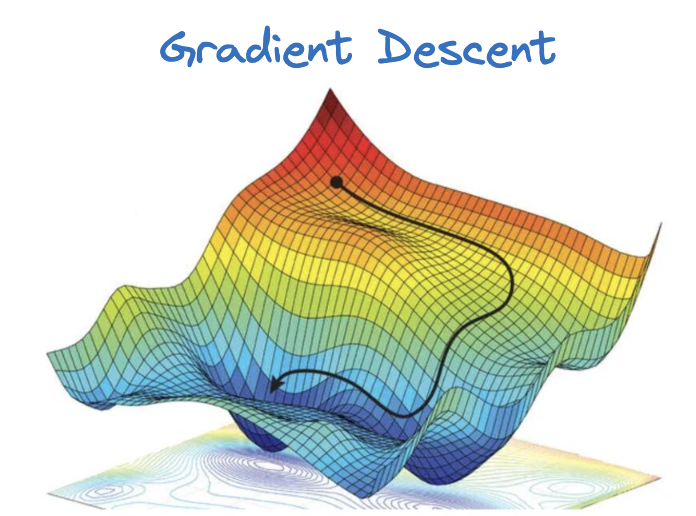

Successive iterations of multiple generations of individuals can help you traverse a multi-dimensional plane, continuously improving your fitness of each successive demographic. This is, in effect, gradient descent. Note that it’s possible to fall into local optima. If you consider biological evolution, there are extraordinary examples in regular life of local optima—species that are incredibly good at surviving in a particular habitat or environment.

Even in humans, we display considerable examples of local optima. Our spine, for example, has evolved primarily horizontally, until only relatively recently we stood upright. It’s not really designed for compression, which explains why back problems are so common. A better design (better optima) would be to re-evolve the spine in a completely different fashion more appropriate for axial loading. However, “re-designing” is simply not possible, since the evolutionary algorithm just doesn’t work that way—it can work with the genes it currently has and subtle, occasional mutations over successive generations.

Figure: A 3-D representation of Gradient Descent. This might depict successive iterations of generations improving the overall fitness. Think of “descending” as improving the fitness.

Figure: A 3-D representation of Gradient Descent. This might depict successive iterations of generations improving the overall fitness. Think of “descending” as improving the fitness.

Mutation

Mutation is where an individual gene within an individual is randomly changed. In the case of this specific problem, consider a “gene” to be a single assignment of an individual to one of their demographics. For example, if Shirley has cats and birds, then she can fit into either Bird or Cat owning demographics. We have to decide whether or not we wish to send her a box for Cat-owners or a box for Bird-owners. In this case, the “gene” is that specific decision—”Shirley gets a box designated for Cat-Owners” is a single gene. Mutating that gene would be switching her assignment, such that she now gets a Cat-Owner box.

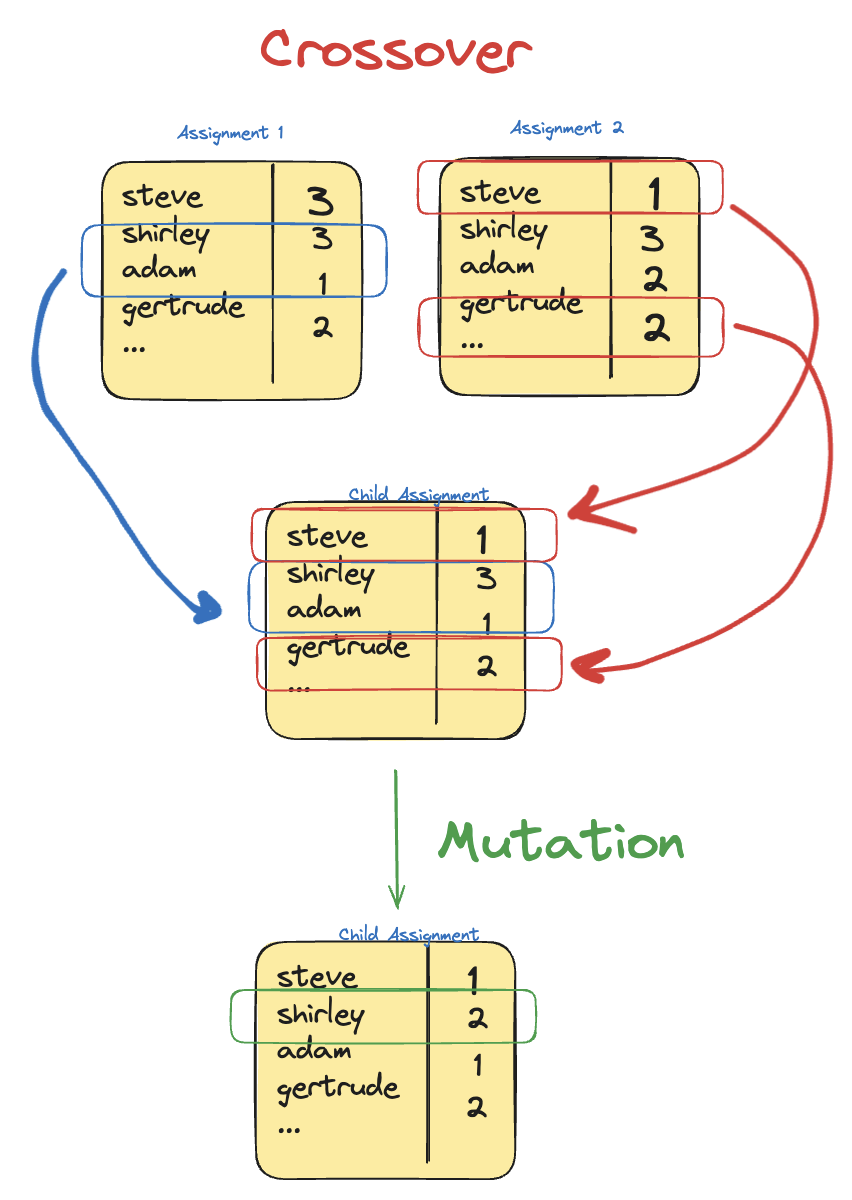

Crossover

Crossover is a case where new offspring is generated, and it takes some percentage of two other parents’ genes. Typically, it’s 50/50, but you can play around with the numbers.

Figure: A diagram showing how Crossover and Mutation apply in this particular problem.

Figure: A diagram showing how Crossover and Mutation apply in this particular problem.

Solution

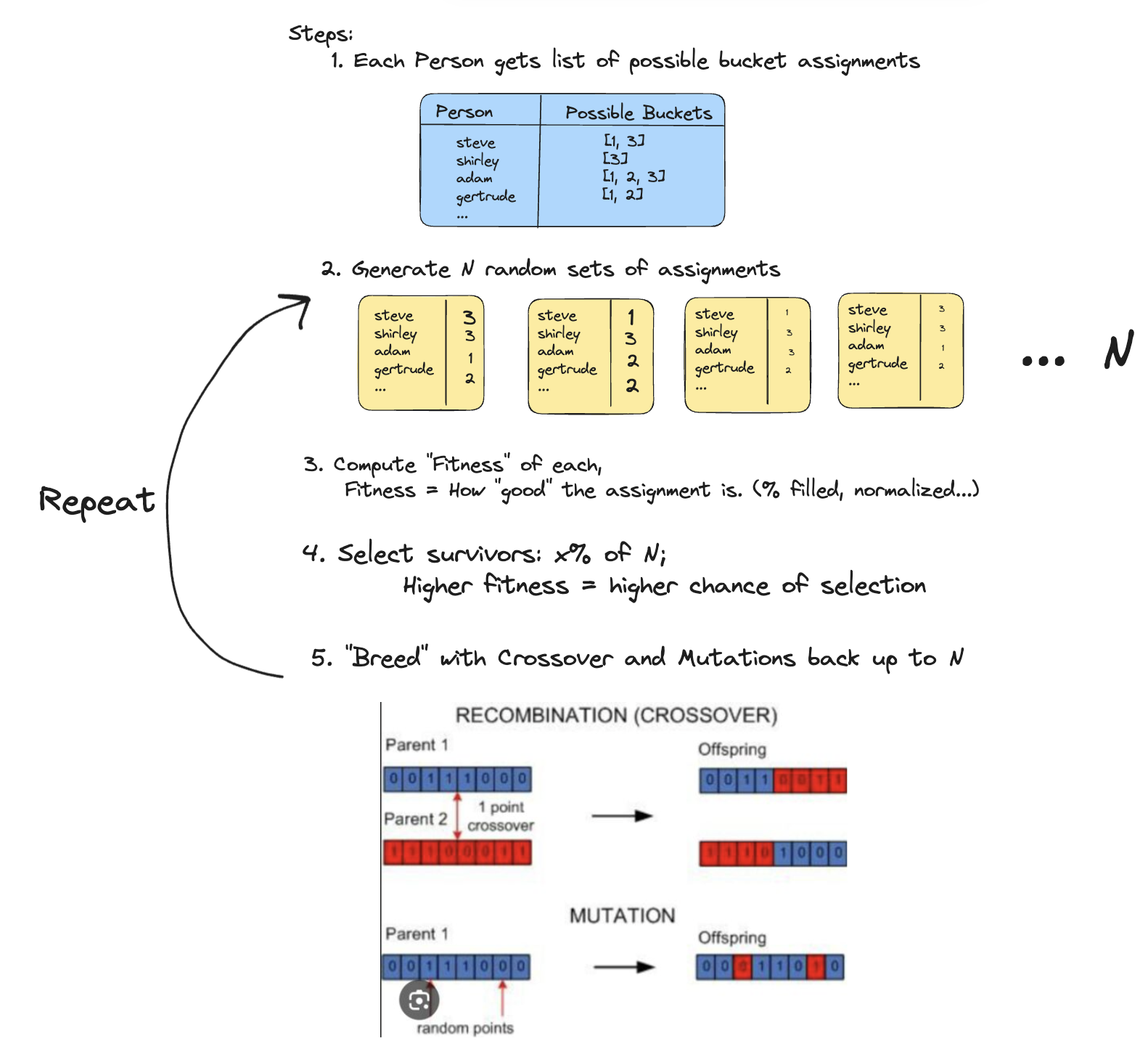

I applied a genetic algorithm to tackle this problem. The process involved the following steps:

- Create a list for each person indicating which of the three demographics they belong to.

- Randomly assign individuals to these demographics N times (N = population size).

- Compute a fitness function based on how “full” each demographic bucket is.

- Cull a percentage of the population based on fitness (e.g., the bottom 90%).

- Repopulate the population through mutation and crossover until you reach the original population size.

Comments